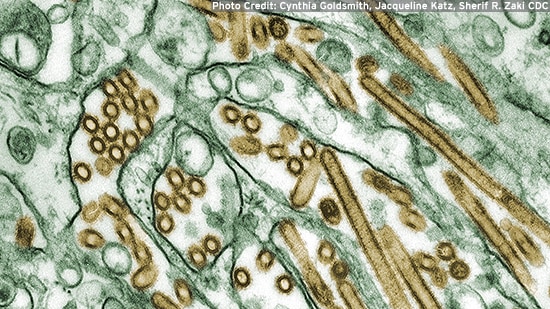

Avian Influenza

What is Avian Influenza?

Avian Influenza is often referred to as Bird Flu. It includes a large group of viruses that can infect all species of birds with varying manifestations dependent on the bird species involved. The transmission of avian influenza to humans occurs only on very rare occasions; the vast majority of avian influenza viruses do not cause any disease in humans. Avian influenza A H5N1 was first isolated in 1997 in Southeast Asia. In late 2003, outbreaks of H5N1 reemerged in Asia. The highly pathogenic H5N1 strain can kill domestic poultry in less than 48 hours. More than 100 million birds were destroyed in an attempt to prevent further spread of the disease. However, disease in birds has also been detected in Europe and Africa. There is global concern that the virus may mutate to a form that is more likely to spread from human to human. Since December 2014, the USDA has confirmed several cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5 in the Pacific, Central and Mississippi flyways (or migratory bird paths). The disease has been found in wild birds, and in commercial poultry flocks. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency have reported outbreaks of avian influenza on farms. The U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention considers the risk to people from these HPAI infections to be low. No human cases of these HPAI H5 viruses have been detected in the United States, Canada, or internationally.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS AND HOW IS IT TRANSMITTED IN BIRDS?

All birds are believed to be susceptible to this infection, but some species are more susceptible. Migratory water fowl appear to be the natural reservoir for avian influenza. The disease can range from mild to rapidly fatal. Avian influenza viruses can mutate from low to highly pathogenic viruses with bird mortality approaching 100 percent with the highly pathogenic H5N1 strain. In birds affected with the high pathogenic strain, a high fever (110-112°F; 43 – 44.5°C) develops rapidly, and the birds become lethargic with a loss of appetite. The comb and wattle of chickens display whitish necrotic (dead) areas of skin, a mucoid nasal discharge develops, and edema (swelling/accumulation of fluid) of the head and neck is often observed. Infected layer flocks significantly reduce egg production and soon stop laying eggs. Death can occur within a few hours after symptoms appear.

HOW IS IT CONTROLLED IN BIRDS?

Control of avian influenza outbreaks involves quarantine of infected farms and destruction of infected or potentially exposed flocks. The disease spreads through direct contact between birds and also from farm to farm by physical means such as contaminated equipment, vehicles, cages, clothing and other articles moving between farms. The virus can also be carried from farm to farm by rodents, flies or other species moving between farms. Droppings from wild birds can also move the virus considerable distances within a short period of time. For the highly pathogenic form, a single gram of contaminated manure can contain enough virus particles to infect up to one million birds. Animal health professionals practice aggressive control measures to prevent spread of avian influenza in domestic poultry flocks. Biosecurity is practiced in most commercial production locations. For example, flocks are raised in enclosed housing to prevent contact with wild birds that may carry the disease. In some countries, such as the United States, poultry destined for slaughter are inspected, which is another key tool for detecting potential disease and keeping sick animals from entering the food supply.

The virus can remain infective for long periods of time in the environment. Avian influenza persisted in feces for more than a month at 39°F (4°C). At room temperature, the virus can remain infective for seven to ten days. The virus is inactivated at a temperature of 132°F (56°C) for three hours and 140°F (60°C) for 30 minutes.i The World Health Organisation, Food and Drug Administration, and Centres for Disease Control agree that cooking all parts of food to more than 160°F (70°C) will inactivate the avian influenza virus.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS AND HOW IS IT TRANSMITTED IN HUMANS?

While avian influenza viruses do not normally cause illness in species other than birds and swine, the first documented infection in humans occurred in Hong Kong in 1997 with 18 illnesses and six deaths. The more recent re-emergence of the disease, as well as human cases and deaths in Asia, has raised concern over the ability of the virus to jump the species barrier and cause a severe disease in humans with a potential for high mortality rates. Human symptoms include high fever, cough and other respiratory symptoms in a majority of patients.

In fatal cases, severe respiratory distress and viral pneumonia were exhibited. Human cases of the disease have primarily been associated with direct and intense contact with live birds. The WHO and others continue to monitor the situation closely to detect conclusive evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission, which may lead to a Pandemic Influenza.

HOW IS IT CONTROLLED IN HUMANS?

As previously mentioned, human H5N1 infections primarily involve close contact between people and sick poultry and their feces. The rare human-to-human cases have typically involved family members giving care to sick individuals. Avoidance of handling sick birds is the primary control to protect people from contracting the disease from sick animals. Infection control procedures similar to those for Seasonal Influenza can minimise human-to-human transfer. These procedures include thorough disinfection of contaminated surfaces in areas with ill individuals, cough etiquette, proper hand washing, the use of hand sanitizers, and wearing appropriate personal protective equipment where indicated. The Food and Agricultural Organisation provides general guidance in "Protect Poultry – Protect People."

REFERENCES AND FURTHER INFORMATION

- Facts About Avian Flu and H5N1

- CFIA H5 outbreaks Canada

- Cooking information

- Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations

- Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy information

- U.S. Department of Agriculture – Draft Avian Influenza Response Plan (1.10 MB)

iSwayne, D.E., Beck, J.R. 2004. Heat Inactivation of Avian Influenza and Newcastle Disease Viruses in Egg Products. Avian Pathology. 33(5):1-7.